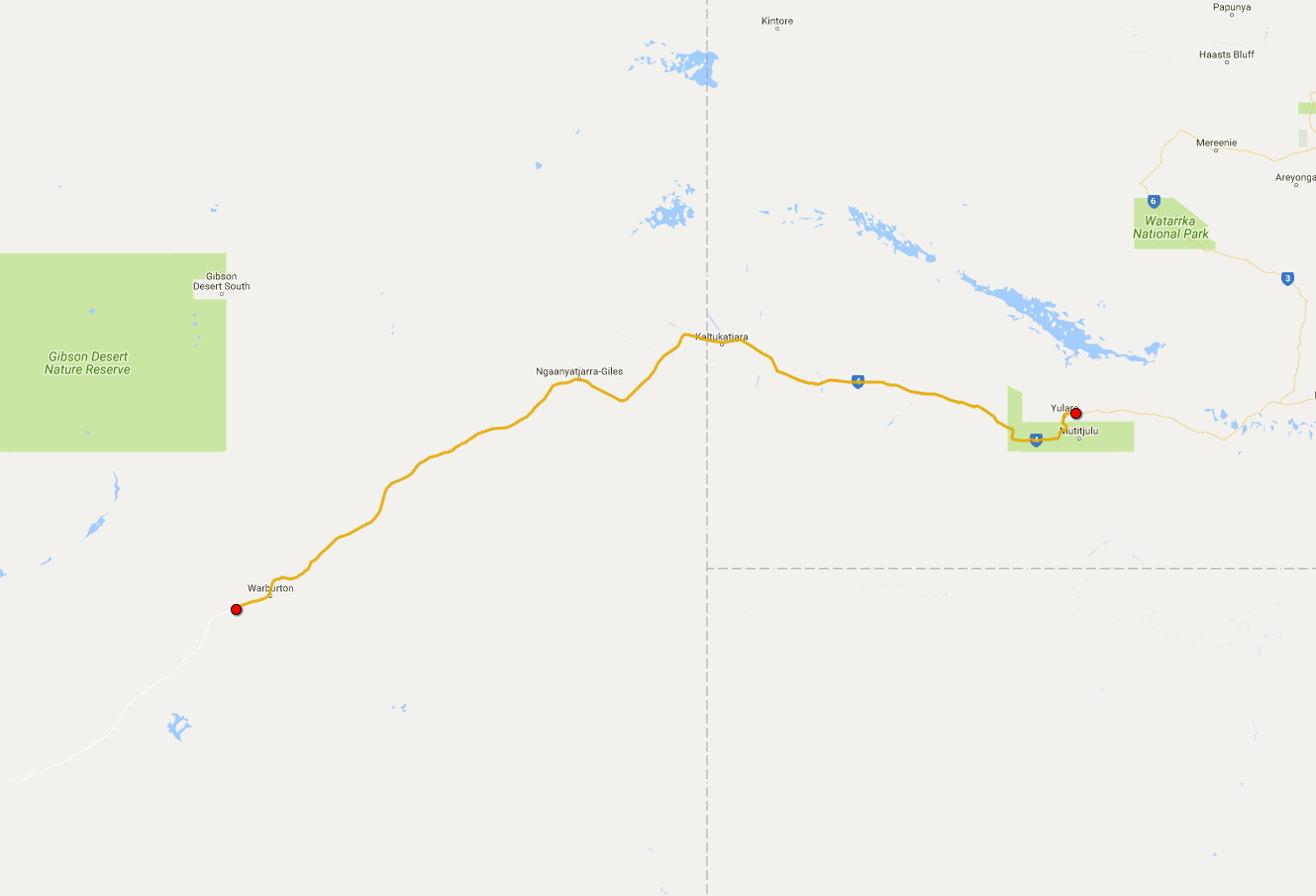

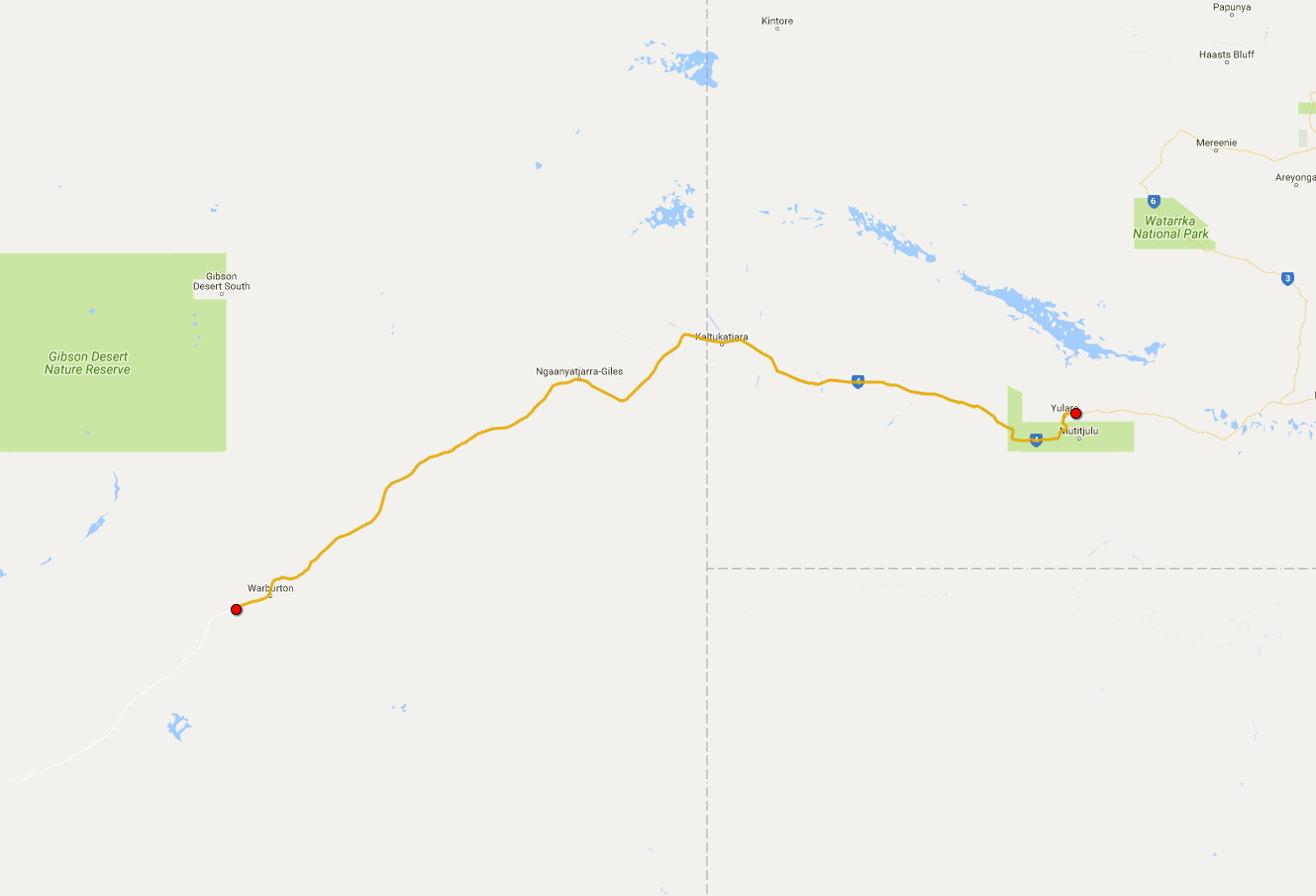

Today's itinerary.

Today's itinerary.

As I've already mentioned, there's another famous place next to the world-famous Uluru, and it's called Kata Tjuta. It means “many heads” in Aboriginal language, which sums up its appearance pretty good. As opposed to a monolith which is Uluru, Kata Tjuta is a whole set of enormous sandstone boulders, looming up quite impressively on the horizon. This is where I'm going today.

Uluru in the morning.

Uluru in the morning.

Kata Tjuta.

Kata Tjuta.

When Ernest Giles, the famous European explorer, discovered these rocks in 1872, he obviously couldn't be bothered with those clunky Aboriginal names, so Mount Olga was the name he gave to the tallest of these rocks. Of course, the real Olga wasn't just a random girl, but none other than Queen Olga of Wurttemberg, née Romanova, daughter of the Russian emperor Nicholas I. The link between the rock and the girl is not too complicated: one Ferdinand Mueller, who sponsored Giles's travels, asked his buddy to do so, and in return the King of Wurttemberg (Olga's husband, that is) made him a baron. This name had stuck with the place for quite a while, and

The Olgas is how they used to call the whole lot. Only at the end of the 20th century they decided to rename it back to what it was known as before. I guess we're lucky that it was

Kata Tjuta and not, say,

Pitjantjatjara.

Last glance at the Uluru.

Last glance at the Uluru.

Kata Tjuta is getting closer.

Kata Tjuta is getting closer.

The entry fee that I have paid yesterday covers both places, so I might as well see this one while I'm in the vicinity. Up close they look no less majestic and intimidating than the Uluru itself, so no wonder they're considered sacred by the Aborigines as well. There's a couple of tourist hikes around, and I choose the Walpa Gorge Hike as my first.

Approaching the gorge.

Approaching the gorge.

Traces of rains.

Traces of rains.

It's still morning, around 10 a.m., but the place is already swarming with tourists, and I have to make efforts now to take pictures without them. Chinese tourists, as usual, are the worst: not only they're the loudest and most numerous, but they spend

ages at a certain spot, making hundreds of selfies per each member of the group. Still, the surrounding rocks overcome it all. They're made of conglomerate sandstone, and each “grain” is the size of my head.

At the end of the gorge there's a tiny brook, along with some scrub and a few puddles of water. Looking back at where I came from, I can see that it's quite a sight in its own right.

A puddle.

A puddle.

Looking back at the gorge.

Looking back at the gorge.

My next hike is The Valley of the Winds. It's a pretty long trail, but I don't take it all, stopping at the Karu Lookout. It starts to get hotter, but the tourists are still numerous, walking briskly in pairs and groups amongst the ancient giant boulders.

Approaching the Valley of the Winds.

Approaching the Valley of the Winds.

Arrived.

Arrived.

The rocks and the tourists.

The rocks and the tourists.

The Karu Lookout.

The Karu Lookout.

Must be the Valley itself.

Must be the Valley itself.

On my way back.

On my way back.

At around 11:30 I leave the park, because I still have to travel west, after all. This is where the bitumen ends. Ahead lies a thousand kilometres of dirt called the Great Central Road: the longest unsealed stretch in my driving career. Feeling a bit nervous about the fact, I deflate the tyres and head onto the track.

Bye-bye, civilization.

Bye-bye, civilization.

The road crosses the very heart of the continent, passing the numerous Aboriginal territories on its way. In order to travel through them legally, you have to obtain two permits: one for the NT stretch (Tjukaruru Road), and the other for the WA stretch (Great Central Road proper). They're free, and I've secured them online back in Adelaide. If you don't need more than three days to travel in these areas, they're pre-approved automatically.

At first the road is not bad at all, and the surrounding arid plains are quite scenic. There are no cattle stations around, not to mention the cattle grids. Not a soul around for many a mile.

At the start of the unsealed journey.

At the start of the unsealed journey.

The surrounding scenery.

The surrounding scenery.

They grade the road every now and again, fixing the washouts and corrugations. Indeed, I meet a couple of graders later—and the road takes a noticeable turn for the worse as soon as I pass them. Corrugations are horrible sometimes. There are numerous creek crossings as well: lucky for me, they're all dry.

The road isn't comfy at all.

The road isn't comfy at all.

As I approach the WA border, I can see the Petermann Ranges slowly rising ahead. They look quite beautiful, and they make for a very pleasant distraction from the corrugations and bumps.

Petermann Ranges.

Petermann Ranges.

Ditto.

Ditto.

Sometimes the road is alright. Sometimes.

Sometimes the road is alright. Sometimes.

At quarter to two I cross the state border. Compared to a full-blown quarantine checkpoint

on the Eyre Highway, it looks underwhelming to say the least. It's still illegal to smuggle fruits and veggies into WA, but it obviously doesn't make much sense to keep a manned outpost in these desolate lands, so you have to dump the said contraband next to the town called Laverton, which is almost 600 kays ahead. It's also a good idea to move your clock an hour and a half backwards, but I'm not on any schedule at the moment, so I can't be bothered.

The state border.

The state border.

The surrounding ranges.

The surrounding ranges.

Still a few bumpy patches to negotiate ahead.

Still a few bumpy patches to negotiate ahead.

Almost as soon as I cross the border, the road improves dramatically. I can easily do 100 km/h there, and even 110 if I like. Easy to see which government is paying more attention to the highway. Deflated tyres also help, and I barely feel any corrugations at that speed at all.

The red desert.

The red desert.

Same.

Same.

The road is fantastic.

The road is fantastic.

At Warakurna, a small Aboriginal village, I stop to refuel. I almost have a mini-stroke when I see the price: $2.40 per litre! It's a bit funny to see all pumps caged and locked, too: apparently, it takes some precaution to keep the local populace at bay. Also, there are numerous signs urging tourists to keep their unleaded petrol well hidden; in fact, they don't even sell it here at all. Instead there's the so-called “opal fuel”, which apparently doesn't give as much high when you sniff it. Quite a place I've gotten myself into!

Once I'm done with the most expensive refuel of my life, I return to the highway. Lesson learned: should have filled my tanks at Erldunda or Uluru instead, when I had the chance. Suddenly a batch of feral camels crosses the road in front of me. They imported them here back in the day to haul cargo around, but the age of the automobile rendered them useless, so they're all on their own here—and they don't seem to mind in the slightest. In fact, Australia is the only place where you can meet a feral dromedary now. Locals aren't too excited about it, though: they're a hassle for the cattle station owners, and they ruin waterholes with their clumsy feet.

Feral camels.

Feral camels.

As I pass Warburton, another Aboriginal town, I stop for today. It is a very beautiful place, completely devoid of people and even the mobile coverage. It's quite unnerving, to be honest; but as soon as I start reading in my tent, I calm down. First day of the dirt road travelling may be considered a success.

The day ends.

The day ends.

Today's camp.

Today's camp.

- Distance

- 573.3 km

- Fuel

- $265.54 (110.6 litres)

Today's itinerary.

Today's itinerary. Uluru in the morning.

Uluru in the morning. Kata Tjuta.

Kata Tjuta. Last glance at the Uluru.

Last glance at the Uluru. Kata Tjuta is getting closer.

Kata Tjuta is getting closer. Approaching the gorge.

Approaching the gorge. Traces of rains.

Traces of rains. A puddle.

A puddle. Looking back at the gorge.

Looking back at the gorge. Approaching the Valley of the Winds.

Approaching the Valley of the Winds. Arrived.

Arrived. The rocks and the tourists.

The rocks and the tourists. The Karu Lookout.

The Karu Lookout. Must be the Valley itself.

Must be the Valley itself. On my way back.

On my way back. Bye-bye, civilization.

Bye-bye, civilization. At the start of the unsealed journey.

At the start of the unsealed journey. The surrounding scenery.

The surrounding scenery. The road isn't comfy at all.

The road isn't comfy at all. Petermann Ranges.

Petermann Ranges. Ditto.

Ditto. Sometimes the road is alright. Sometimes.

Sometimes the road is alright. Sometimes. The state border.

The state border. The surrounding ranges.

The surrounding ranges. Still a few bumpy patches to negotiate ahead.

Still a few bumpy patches to negotiate ahead. The red desert.

The red desert. Same.

Same. The road is fantastic.

The road is fantastic. Feral camels.

Feral camels. The day ends.

The day ends. Today's camp.

Today's camp.